Welcome back, delegates! There are three interconnected themes today and we have stories for them all, which you can read below.

The themes are: Adaptation, Agriculture & Food Systems and Land.

Adaptation: Penang Fairhaven – a visitor’s guide by Steve Willis

Where do we want to be in 40 years’ time?

This is a clear vision of an awesome future city, in a world where many issues are addressed head-on. Press the read more button to dive right into the story.

N.B. Everything in this short story is fictional (including appendices) but we’d love to make it fact.

Read More

Fly through this amazing city in 2062. See the amazing climate solutions.

This is the METATMHOLOTMGLYUIDETM introductory virtual tour of the city and its history. (if you are having trouble with the HOLOglassesTM, please press the help button on the side and a real person will be along straight away to help you.)

I am your guide, known to most of you as Miss Chan. I have lived and worked in the city since it was first built, 40 years ago. I will show just a few of the many highlights of the city and also explain a few housekeeping tips which will make your trip much more enjoyable.

We are now hovering above the north dyke, facing the Malacca Strait. The water is 2 metres higher than it was when the project began in 2025 and I started my first job as a junior engineer on the Bazalgette pumping station.

If we turn and face south, we can see the new city of Fairhaven laid out beneath our feet, a beautiful poly-cultural mixture of 18 districts from all around the world, the Arab Quarter, Little India, NewNew Orleans, New Venice, China Town, Russland, NewNew York, Heart of Africa, New Amsterdam and more that you will explore. It is home to 10 million people.

Let’s swoop down into NewNew Orleans, through the French Quarter. You can see the beautiful wide boulevards filled with trees, pedestrians and bikes. There is a San Francisco style trolley car and numerous stops on the LRT which will whisk you anywhere in town. This popular ‘Bourbon Street’ stop has dozens of cafes, 4m below sea level, links to the river bus which travels the canals to many other parts of town. These re-created quarters are a bittersweet reminder of the many beautiful places that have already been lost to sea level rise.

We’ll have a seat in this Mamak stall for a moment – there are loads around the city. I am, of course, biased, but Malaysia makes some of the best food in the world: Nonya, Malay, Indian, Chinese and every blend in between. Be bold, you’ll find something you love.

Housekeeping point 1. Water.

You will see that water is provided in jugs. The tap water is totally safe to drink all around the city and the region, so there is no bottled water. There are also no single use plastics – all containers are melamine or Tupperware which are returned to the ‘ReUse’ slot at the municipal garbage collection points. You can pick up or refill a water bottle at any food outlet for free – it is pretty hot here, so please make sure you stay hydrated.

In your hotels, B&Bs, hotels and homestays, you are welcome to take long showers, and even baths – a rare treat for many visitors. Unlike most cities in the world, Penang Fairhaven has no water restrictions because of the large reservoirs and the drain separation. Rainwater joins the canals and onto the reservoirs, sewage is collected in a dedicated high solids system and ‘grey’ water from showers, washing machines and domestic use is collected separately. This grey water is treated and then pumped inland to provide irrigation for the crucial rice fields north and south. We are constantly diverting fresh reservoir water into this system, so you may as well enjoy the thrill of an unrestricted shower first!.

Let’s continue. Gaining height, we now head along the great North Dyke which prevents flooding of the low-lying lands of Kedah & northwards, protecting the crucial rice fields – all the more important after the flooding of so much of Vietnam, Bangladesh and parts of China. The new biochar-based farming techniques have boosted yields three-fold.

You can see the fleets of Snow Geese Zeppelins which are recharging from the reservoir floating solar arrays. This is their first stop of 12 on their long journey from the famous Equatorial Zeppelin yards around Singapore to Siberia and the Arctic.

The Snow Geese Zeppelins spend the endless summer days putting out peat fires and the frozen darkness of winter helping to refreeze the Arctic ice. Thousands of these nearly autonomous craft are working on the top of the world and hundreds of new zeppelins join them every year, expanding the fleet and replacing the losses. They form one of the biggest climate and albedo restoration projects attempted so far.

Further inland you can see the Regional Fast Rail Network that many of you travelled on. Most of it travels on land that is at least 20m above sea level and is secure for generations to come.

Beyond that, you can see some of the palm oil plantations. These have also become major carbon sinks after switching practices and putting millions of tonnes of biochar into their soil. An impressive transformation.

Let’s fly out over the Malacca Straits. Below us are many ships, travelling more slowly that they did in previous decades. Interestingly, there are still many oil and LNG tankers and they are all running on heavy fuel oil. The fossil fuel industry is smaller, but is still important. You will be pleased to learn that despite this, the ships are carbon negative, as they are used as satellite-guided ocean-nutrification platforms – fertilising carefully monitored sectors of the ocean to maximise primary productivity, managing algal blooms and delivering an additional beneficial role with an existing resource. You will see that some are also towing a high zeppelin as a water spray platform from which to make reflective clouds – one of our many ongoing climate solution trials.

Heading back to Penang, you will see the fast Wigetworks https://www.wigetworks.com/copy-of-take-off-1 ferries which connect the coastal towns of Malaysia, Sumatra and across the region. They are a lot of fun – the closest most people will ever get to flying in a real plane these days. They are all electrically powered, fast, and remarkably safe.

We are now crossing the first OceanOrchardssite in the world. It was my third real job, installing the seabed structures from the supply boats and then working with the fishing communities that learned to work with the OceanOrchards and then care for them. This a great day out, either in the nearly-a-submarine or actually diving amongst the submerged structures of the OceanOrchards themselves. You will be amazed at the abundance of fish, corals and other sea life. The more practical amongst you will be impressed by the carefully controlled fishing techniques that allow ongoing substantial fish catches while ensuring fish populations which are 20 times that seen in open waters.

There are now thousands of these sites around the world and as well as producing a large proportion of the fish consumed, they are truly sustainable and are massive carbon sinks.

Just in land from the OceanOrchardsand seagrass meadows, you will see the inundated west coast of Penang. Although controversial it was decided that the land protected by the necessary seawall was too small to justify the construction. Instead, the area has been turned over to mangroves. The northern section is fully natural, and a carefully preserved gene pool of truly wild mangroves. The southern section is the new mono-clonal TurboMangroves which grow 5 times faster and are coppiced for biochar. The wildlife living there seems indifferent to this, and is thriving. We are running a trial to see if these new mangroves can form the central reinforcement for new dykes that could be literally grown in place and then backfilled – watch this space.

Housekeeping point 2. Freedom To and Freedom From

Fairhaven is still very much a Malaysian city, but with 18 distinctly different districts, Fairhaven is also one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world. This diversity is the reason many of you have come here. However, this massive diversity does bring some complications. We want everyone to be free to do more or less whatever they want and to be free from criticism or restriction Following the simple principle of: Freedom To and Freedom From.

This means that while you can do pretty much whatever you like within the guidance of the law, you can’t do it everywhere at all times. This separation in time and space (A classic Triz solution) allows us to all live alongside one another with joy rather than friction.

For example, in the North America district, there are numerous distinct neighbourhoods. The NewNewOrleans area is very free and easy and particularly popular amongst visitors. The Amish Community is also fascinating and well worth a visit, just not in the same attire or the same mindset. We residents have come to terms with this, but we realise it is a challenge for visitors.

Naturally, there is an app for that, which is downloading on your phones and AI assistants. If you have a Bluetooth tooth, it will automatically update so you can get hints and tips by sound bone-conduction directly into your head. The system guides you through what you can and can’t wear, do, or say in the various districts.

While this may seem restrictive, it is also powerfully liberating. The short shorts and spray on attire popular with tourists this season are welcome in some areas, but deeply offensive in others – which may only be one street away. This allows visitors to avoid making embarrassing faux pa’s and allows people to live in their own areas without too many glaring clashes.

Moving on: We are now at the southern dyke and hovering over the old international airport with its 4 massive runways. They are still in occasional use, but the area is now the largest aircraft museum in the world. I know the old-tech geeks amongst you will love this place (I know because I am one too). Looking north, you can see the two large freshwater reservoirs which still give Penang an island feel – there are loads of lovely lakeside resorts you can enjoy, without the inconvenience of the jellyfish protective suit that is needed to swim in the sea.

We now head into the city and to Ocean State Plaza. I know this will be a highlight for many of you, especially those who consider themselves foremost citizens of The Ocean after it handled their climate refugee relocation and treated them respectfully throughout. The 19th anniversary of the formation of ‘The Ocean as an Independent State’ is next week, and you will be able to join the celebrations. All are welcome – we are all citizens, after all.

It still amuses me that ‘The Ocean’ became an independent state as a result of a short story published in a climate almanac that was written ahead of COP27, as KSR’s Ministry of the Future had been in COP26. It was picked up and cherished by some delegates and then became a memorable episode in the Netflix ‘Climate Mirror’ series which looked at both positive and apocalyptic visions of the near climate future. This was followed by the largest global social media movement seen and a huge popular push to get the land governments of the world to accept the proposal. The revenue that The Ocean receives for present and past services rendered has provided the funds for enormous ocean and coastal restoration projects.

I was one of the first members of The Ocean team, before independence was agreed, and it is the proudest part of my life. Fairhaven is one of 5 Ocean capitals around the world, and I know that many of you hope to visit them all in time. The Ocean as an Independent State is an astonishing collective achievement, and allowed so many ocean, climate, and refugee-related shared calamities to be addressed from a bigger perspective.

The Ocean coordinates the Ocean Orchardsand the other Ocean CDR work as well as handling 150 million climate refuges so far. A number which is rising every year. The largest carbon drawdown has been through The Ocean, as reforestation and CCS has struggled. The Ocean is also coordinating the refreezing work in the Arctic – we hope to achieve the maximum summer ice extent in 10,000 years very soon. Another team is coordinating the even bolder plan to stabilise the ice sheets in Antarctica – following a plan very similar to the one outlined in Kim Stanley Robinson’s classic book, The Ministry for the Future.

I will leave you here and let you explore the city virtually and in person at your leisure. All the things we have seen today and many more have links and their own METATMHOLOTMGLYUIDETM tours. I am the guide on dozens of them, so will see you again soon!

| THE OCEAN – AN INDEPENDENT STATE In 2031 The Ocean declared independence from The Land and was accepted into the UNThe Ocean sought independence in order to resolve its own problems. It recognised that the neighbouring countries could never truly put the interests of The Ocean on a par with their own.At independence, the Ocean started to charge for services that have traditionally been provided/taken for free. Levies of 1% on fishing revenues. 1.0% on shipping. $1 per tonne for CO2 sequestration. $10 per tonne for effluent. $100 per tonne for plastics. Managed carefully to avoid advantage being taken of these low charges. The services provided by The Ocean are valued at trillions of dollars were being taken for free. The Ocean makes extensive use of global fishing watch tracker and satellites and uses this revenue to fund MPAs and other critical restoration activities. The Ocean assumes full authority of the open Ocean. 50/50 of EEZs. 25% of coastal waters. People of all nations can become citizens of The Ocean. The bill for each land-country is calculated and posted regardless of whether they are paying or not. Four numbers, from the date of the first UN conference on the Oceans, total from the start of the industrial revolution, annual total and per capita. This highly controversial approach raises the profile of the issues The Ocean faces and help focus the discussion on how much the actual amounts are, rather than whether or not it is reasonable to charge for the services. |

This was another idea picked off the cutting room floor. It began many years ago with a light-hearted conversation over lunch with the head of sustainability for a major US bank. He pointed out that America only became great after it declared Independence from the colonial power. By extension, The Ocean can only resolve its problems and become sustainable by declaring independence from the surrounding countries which currently use/take its resources for free.

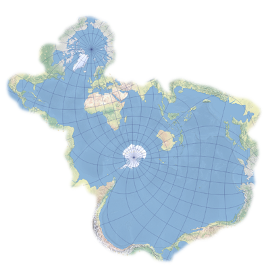

I was amazed at how quickly this turned from an idea in a fictional TV show about the near future to a whirlwind ‘Our Ocean’ social media campaign and then into a reality. The story originated from a Cli-Fi – climate fiction – competition at COP27 and was one of three that went on to become Netflix programmes, a climate version of Black Mirror. I love the map, which is the flag you all now know.

Penang is one of 5 Ocean Capitals, along with four other cities in Madagascar, Iceland, Panama and Hawaii.

Charging for the services that were previously used/taken for free gave The Ocean the revenue that had never been available before to sort out its own problems and those of the coastal countries. A bright light in a bleak time. There was a lot of resistance initially, but the massive public support through social media for such an out of the box idea quickly won over a small, pivotal group of countries that was just big enough to get the idea off the ground. Switzerland, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan were keen founder members.

Many people identified with The Ocean as the ultimate underdog, the largest occupied, unrepresented territory in the world. Journalists were particularly supportive – in a time where fake news continued to be a problem, it was thrilling that a fictional story could go on to have such influence.

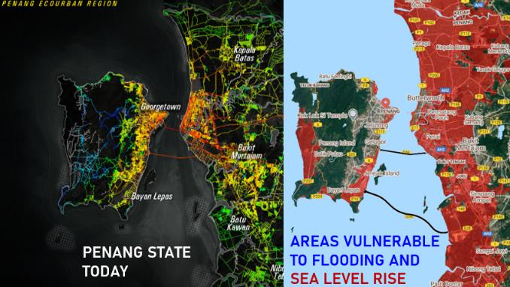

Before the Fairhaven project was conceived, Penang already suffered from flooding.

In 2025, the decision was made to build early, assertive protection for Penang & the surrounding areas. Otherwise, this low-lying area would be inundated and reduced to low lying salt marshes. If nothing was done, a large proportion of the state would be lost. An unattractive situation. How was this grim fate be avoided? How had others dealt with this in the past?

Over the last few hundred years, the Dutch have built a huge network of dykes and Polders to recover land from below sea level. They pumped water out with windmills before the days of electricity. This was a well-established technology.

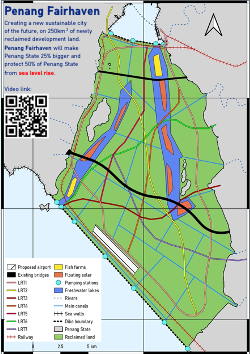

Penang Bay was an ideal location for a similar project. Two large dykes were built across the north and south of Penang Bay, enclosing an area of 250km2 – an area nearly as large as the island itself, and adding another 25% to the area of the original Penang state. Penang’s geography is uniquely suited for this approach, with a large area of very shallow mudflats enclosed on both sides by dry land.

This new polder area was pumped out to create a large area of land for development with two large fresh-water lakes. 18 new development areas were created, joined by a network of broad canals for transport, drainage and recreation. The lakes became the new waterfront of the island, with resorts, hotels and recreational facilities in clean fresh water, Penang has an island feel. Penang is well connected to the regional rail network as growing ‘flight shame’ increases demand for low carbon travel options.

The Penang Fairhaven land provided a clean sheet on which to build a super new sustainable city for a rapidly changing world – an architect’s and town planner’s dream – and an opportunity to address all 17 SDGs at a massive scale. This new city was laid out with cycle ways, pedestrian zones, solar panel covered walkways based on lessons learned in other countries. Each self-contained district is designed to have distinct feel, like little India & the Arab quarter, but on a global theme – travel the world without ever leaving Penang. The impending catastrophe of sea level rise was boldly embraced and used to build a new Penang, a new Pearl of the Orient.

Appendix 3 Penang Fairhaven Maps

Read Less

Agriculture & Food Systems: The Desert Spiral Initiative by Howard Gaukrodger

An Egyptian farmer leaves his land because of drought, and in his travels sees a potential solution to the problem. Luck crosses his path with someone who can help deliver this bold plan

Read More

Zdan was working extra hard this season, keen to impress his wife, desperate to feed the family. Meagre crops of beans, magaria, dates, figs and olives enriched their aysh, but harvests were pitiful. And even when they treated themselves to a shank of goat meat, Zdan knew what Tasa was thinking.

Thank you, God, for this precious food. Thank you, husband, for tilling the soil that has made such sustenance possible… but this is no life for our son. Aksil is worthy of responsibility. No family will offer their daughter in marriage to a farmer of goat dung.

The only solution was for Zdan to leave, to travel away from their dusty, clay-brick home and find well-paid work in Cairo. For Aksil to advance his education in the city, he would need money for food and accommodation. Zdan had to go.

“Husband, we do not want you to leave, but by God’s grace, Aksil can tend to our crops, and I can clean our house and herd our goats. But stay away too long, and our crops will die, the goats will starve – and we will follow.”

#

With the arrival of the new moon, Zdan found himself in Cairo, six hundred kilometres to the east. It was a difficult first day.

“May your body be infested with the fleas of a thousand camels!” he cried.

But the thief, no taller than a donkey’s hind leg, had already faded into the fog of the market throng. Zdan was unaccustomed to the chaotic life of the city. Counting his money in a public place had proved a woeful mistake. His family’s savings were gone, and with it his means of survival.

With only a crust of bread and dried fruit in his bag, a moment of foolishness had condemned him to the life of a beggar. How could he ask for a job when he smelt like the arse of a pig? Squatting with his back to the sun-baked wall, he winced at the shame he had brought upon his family. He sought consolation in his inner thoughts, but the pain was too fresh to be tempered. His head fell to his knees and he wept. For a time, self-pity sheltered him from the roiling crowds, the blaring horns and the dusty streets. But then he heard the muezzin‘s call to prayer – a chant that discovered within him one final drop of resilience. The afternoon asr was sacred. His spirit was not yet broken. He would not allow himself to be doomed to Jahannam. Turning to face the Qibla, he recited his prayers. And there, in the rat-infested gutter of a cluttered city street, Zdan’s life changed.

#

It was the scent. Bitter-sweet. Different. Expensive. It hung in the air, stuck to the dust, crept up his sandy, sweat-stained haik and made its home in his scruffy, black and white turban. So out of place was this scent that Zdan put aside his sorrows and peered up. Against the diffused sunlight of the yellow sky, the silhouette of a tall, well-dressed man arched over him. Without words, the silhouette proffered a bladder-flask of water. Zdan accepted the gift. Now, he was indebted to the silhouette.

“Brother,” said the silhouette, “I need workers. There is strength in your shoulders, and now I see endurance in your weathered face and honesty in your eyes. Come walk with me. I travel to Aswan tonight. Join me and I will assure you of a job that will support you and your family, God willing.”

Zdan looked to the sky and cried, “Allah be praised!”

#

A year had now passed since Zdan’s arrival at the silt-panning labour camp in Aswan. The silhouette with the patent leather shoes and bitter-sweet aftershave was long gone, his task of finding cheap labour complete. He had honoured his word and had given Zdan a job, but the work was a mere scorpion spit from the depths of slavery.

For the second time, Zdan had suffered the pain of naivety. He and his band of rag-tag workers were just one raht in a crawling army of sunburnt panners, sifting for gold in the silt of the Nile. With his one year of seniority, Zdan was now spokesman for his group, but everyone answered to the camp’s leader, the zaeim. And no one was immune to the zaeim’s fits of rage and the whip of his bootlicking henchmen. But Zdan was earning money, and would soon have enough to travel home. He could give his family the money he’d lost and a heavy purse for his son’s education. The day came and the zaeim called him to his tent.

“Brother,” said the zaeim, “here is your money.”

Zdan counted the torn and muddied notes. “Brother, this is only half of what I am due.”

“Be grateful for what you receive. The rest you will have on your return.”

That evening, before the sun dropped over the horizon, Zdan wandered up the west-facing hill overlooking the camp. From the wind-carved ledge of a diamond-shaped rock, he reflected on the scene below. Discarded silt lay drying in circles, protecting the workers within. Plants grew in the semi-dry, brown piles, firm enough to support life, wet enough to nourish it. He smiled. If only the Nile ran through Siwa.

With night but a whisker away, he clambered down, praying his sandals would hold. Tired from his labours and the arduous walk, Zdan paused and took a breath. As he looked up, he was struck by a family of spherical, red clouds drifting north. Balloons! How peaceful. One day, I will buy Aksil a ride in the greatest balloon of all!

Despite his half-share wage, Zdan slept well that night – thoughts of his family uppermost in his mind. Within 24 hours he would be able to embrace them.

#

“Dear husband, I know you will be sad, but your son has left home.”

After her greeting, these were Tasa’s first words on his return to Siwa.

“We have little food, and our land is poor. He has turned 18 and vowed to earn money for our family. Only last week he left for Cairo to seek work in the world of tourist hotels.”

Zdan was distraught. A year of hard labour, and now his son was gone. While tears fought with his pride, he knew it must have been worse for his wife. He’d taken their savings and they’d thought him dead.

#

The moon waxed and waned, but Zdan never seemed to finish tilling and planting. He had hoped to till the strips of land quickly, so he could leave to find his son and give him his silt-panning earnings. But the ground was exposed, rock-hard, unforgiving. Wind-blown sand smothered the seed beds, or broke the shoots.

“Tasa,” he said, one morning. “It is a sin to sit on the money I have earned, when we could use it for the benefit of many. I have an idea. We will invite our friends and members of the local community to join us in a project of mutual benefit.”

His wife looked at him, eyes wide. They had never been close to their neighbours, and this far from the Siwa mosque, the local community was as real as the mirage of wealth.

“And what is this project?” Tasa asked.

“It is a crop spiral! The outer rings will protect the inner rings. I saw such a thing in the work camp, though it was us that the mounds of discarded silt protected!”

Tasa nodded slowly, her husband’s wisdom a shining light in a barren landscape.

#

“Keep going!” Zdan cried to the tractor driver. “One more circle!”

And before the sun had set, the final ring of the massive furrowed spiral was complete. The land that would have taken Zdan’s family two months to till by hand was ploughed in one day by the tractor. And for the loan of the tractor and plough, he had paid just two goats.

“Ahmed,” he said to the tractor-owner, “I do not know where you obtained this magical plough, nor why it is called a ‘dolphin’, but God thanks you, I thank you. As agreed, I will pay you the equivalent of six goats if you will plough the land of our neighbours.”

#

Within the following week, Zdan and Tasa exhausted their stock of goat dung, lining only the first ring of the spiral farthest from the well.

“Our fertiliser is gone, Zdan. We need a hundred more goats to fertilise all this circle.”

“Or the silt of the River Nile.”

“You talk in the riddles of a charlatan,” Tasa smiled

“Forgive me. Let us go inside. We will wash, pray, and I will share with you the details of what I learned in Aswan.”

#

The local community worked tirelessly as a team to sow and irrigate their crops in mysterious spirals. Children looked on, marvelling at the train of bucket-loaded donkeys, carts and tractors shunting to and fro, taking water from the community well or from private storage tanks.

Finally, after days of back-breaking work, Zdan was free to leave for Cairo to search for his son. And once there, he trudged from hotel to hotel asking after Aksil. Occasionally, a receptionist would look at him with disdain, as though saying: ‘Goat-herder from the desert. What’s he doing here?’

But in one hotel, a lady of evident sophistication overheard the exchange at the counter and approached the modest farmer. She introduced herself as ‘Beatrice’, and a conversation ensued which consumed Zdan’s thoughts as a starving man might consume a leg of freshly roasted lamb.

“Crop spirals, community ploughing, goat dung fertilizer… and such a small amount of water. Fascinating!” said Beatrice.

“Mm,” replied Zdan.

“Eh bien, I am very interested. Perhaps, if it is convenient for you, we could travel back to Siwa, and you can show me how your trees and plants are growing.”

“It would be an honour,” said Zdan.

“Oh, and I would like to bring with me a colleague. He also works for the Trans-Sahara Climate Mitigation Organisation. He has a lot of contacts and perhaps he could help find your son.”

#

The bus ride was perhaps a little uncomfortable for the French lady in her tailored clothes, but she was humble enough not to complain.

“Magnifique!” exclaimed Beatrice, as she inspected the family’s crops. “And you planted these crops and trees just five weeks ago? Magnifique!“

The next time that Zdan heard from the lady was when a courier arrived with a letter. Without access to the Internet, the family customarily relied on the relay of spoken messages, or at most, a written note. A courier message heralded either something very good, or something very bad.

‘Dear Zdan, I have explained your farming technique to my colleagues, and have shown them pictures of the results. They are very interested in meeting you in Cairo. Your combination of using the so-called Delfino Plough, the crop spiral, and, most intriguingly, your proposal to use river silt as a fertilizer has made a considerable impact. We believe we could build on this with modern technology and use it to plant millions of trees. We will, of course, refund all costs of your journey, and board and lodgings…’

But while this news was important, it was the next paragraph that really excited Zdan.

‘… We also have news of your son. My contact tells me he was indeed here in Cairo. It seems he worked for a short time at the Hotel Great Sands as a kitchen-hand. Regrettably, he moved on and we have no further details.’

Within 24 hours, Zdan was heading back to Cairo, this time on a train. Tasa had trimmed his hair and beard, insisted he wear a fresh headscarf and traditional haik. She sensed this was something big and they could not lose face.

Having visited the Hotel Great Sands and confirmed the information provided by Beatrice, Zdan shuffled off and booked a room in a poorer quarter of the city. The following day, he went to meet the ‘climate lady’.

“Good morning, Zdan! Welcome. A glass of water, perhaps? Let me introduce you to my colleagues and business partners.”

Zdan was dumbstruck. Before him was not only the lady he’d gone to meet, but a roomful of businesspeople and politicians. He sat, as a fresher might sit amid a roomful of Harvard professors.

“We’ve been discussing your method of planting.”

Beatrice talked for several minutes. By the time she’d finished, Zdan thought they were going to re-green the whole of the Sahara.

“I am honoured you find my idea so interesting. But I am unclear…” he started.

Several men in the room grinned, and debate continued, entirely ignoring the farmer from Siwa. It was only when Zdan risked raising his voice to contribute a bold, new idea that he attracted full attention.

“Air balloons?” one of the financiers responded. “You want to float air balloons across the desert and drop silt from the basket?”

And then everyone wanted to talk at the same time.

The spokesperson for the Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation banged the table. “The idea may not be as far-fetched as you think. According to my advisor, here, there are powered airships that can carry up to 160 tonnes of cargo. If this cargo happens to be silt that has been dehydrated by, say, 80% to 32 tonnes, then such a vessel could carry the equivalent of 800 tonnes. And we can fertilise many spirals with that.”

“Navigation? Altitude? Accuracy of the drop?” asked the representative of the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation.

“Yes, there are things to work out, but with GPS navigation and a flexible pipeline, it is not impossible,” said the former spokesperson. “But how can we irrigate these spirals, and where should they be located?”

Beatrice leaned over. “Ecoutez. Listen Zdan, you may wish to leave now. We have much to discuss. If you go to reception, you will find an envelope waiting for you. I will contact you this evening.”

Zdan stood, nodded to the group, then went to collect the envelope. Inside was a mobile phone, a receipt for the advance payment of three nights’ accommodation at Beatrice’s hotel and a note: ‘I believe your ideas will prove to be worth far more than the cost of a phone and accommodation, but please accept this as a token of our appreciation. Regards, Beatrice.’

#

At 8.30, next morning, Zdan was back in the hotel lobby. Beatrice arrived and smiled with an air of complicity.

“We have a breakthrough, Zdan! Let me update you before we go to the conference room. The Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, the European Investment Bank, and all the other parties recognise the merit of your idea, and all agree that we should develop a proof-of-concept model.”

Zdan placed his hand across his heart. “Allah be praised.”

Taking a map of Egypt from her case, Beatrice continued. “Rather than reinvent the wheel, our proposal involves combining existing projects and technology with your ideas. We’ve called it The Desert Spiral Initiative.

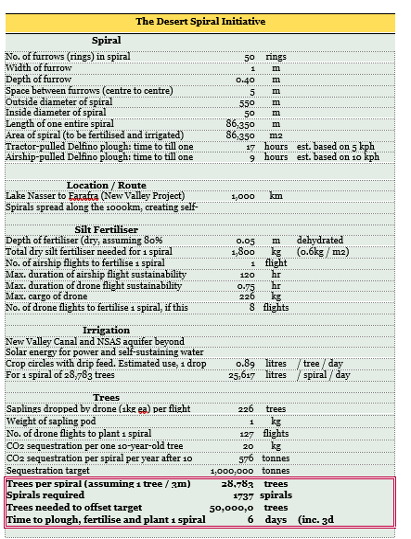

“We will plant a chain of 550-metre spirals across the desert, enough to green the desert for a thousand kilometres! It will run from the Toshka lakes to the Farafra Oasis.

“Dehydrated Nile River silt will be channelled into the furrows by a hose from the airship. Finally, drones will fire pods of fertilised saplings into the tilled soil and rehydrated silt bed.

“For irrigation, we propose a network of small wells, extracting water from the New Valley Canal and the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer – one well per ten kilometres. Well-water will be pumped using solar energy. One of the many advantages of your idea, Zdan, is that it will use only a fraction of the quantity of water that lineal and random planting use. And it’ll take only 3-6 days to plant one entire spiral! Imagine how quickly we can transform the desert – 1,737 spirals to plant 50 million trees! A million tonnes of CO2 gone! Egypt will be the envy of the world!”

“Inshallah!” said Zdan. “But your ideas are too complicated for me. I see I am no longer needed and shall continue the search for my son.”

“Very well, Zdan. But allow me to give you this document. It is a summary of the project for discussion at the meeting this morning.”

Zdan glanced at the paper.

“My friend, where are the people? This project is for the whole of Egypt: farmers, nomads, people of every race and religion.”

“But Zdan, this document is for the decision-makers, our leaders and investors…”

Zdan roared, “It is for the people! It is they who will make it a success! Build a house, or a whole village, in the middle of each spiral… and a mosque, classroom, or medical centre, every one hundred spirals. The people will tend to the trees, and in exchange, they will have free power from the sun and free food and lodgings.”

Beatrice was stunned. She didn’t expect this outburst. Yet, she had to admire him. The need to attract people away from the Nile to inhabit the desert was an ambition that many a president had expressed.

“I will put your ideas forward at the meeting, Zdan.”

The wise farmer nodded and turned towards the door.

“Farewell, Zdan. I’m sure we will meet again. Bonne chance in finding your son.”

#

It didn’t happen overnight, but Egypt and the world needed the project to go ahead. At the press conference just eighteen months later, a letter of intent was presented with all project details. It included the final ideas so forcefully put forward by Zdan. His name even appeared in the report, and in due course, he would be recognised as the innovator of The Desert Spiral Initiative.

With Zdan’s renown spreading throughout the country, it was almost inevitable that Aksil would one day read about the project and come across his father’s name. But only when he’d earned sufficient money for his parents to be proud of him did he travel home to Siwa. And he was not alone. While he had found a permanent position at a hotel in Luxor, he’d also found a young woman by the name of Sakina. And two years to the day since Aksil had left home, the family celebrated their marriage. Their reputation was growing, and so was that of Egypt.

Read Less

Land: Groundup by Elizabeth Kurucz

A sporting hero returns to his withered roots. Ambition takes a young man from the land and into a parallel world of supplements, injury, painkillers and short-term goals. It finishes him. When he returns, he realises the same has happened to the land. He resolves to fix them both.

“The soil is the great connector of lives, the source and destination of all. It is the healer and restorer and resurrector, by which disease passes into health, age into youth, death into life. Without proper care for it we can have no community, because without proper care for it we can have no life”.

Wendell Berry, “The Unsettling of America”

Read More

My oldest kin were in the soil. So many relations, all of them holding tight together, rich, like chocolate cake moistened with beetroot and no need for second helpings.

Dust bowl dirt never wearied this land anymore. It blew over our house for years, a relentless cloud of misery from nearby fields deserted by neighbours who had surrendered to the not so common wisdom of agrochemical companies that specialized in short-term solutions for urgent situations. These engrained habits were a loan made against future generations that could never be repaid; a thought, a shadow, a plague that passed over us and slowly dissipated. We came to the brink but were spared the ruin of our own topsoil.

The more I think about it these days, the more I realize there was always someone trying to wring one last ounce of something out of me.

Except for Amy.

In my earliest memories, we are playing together in the mud, walking barefoot, letting it squish up high, soft mountains in between our toes. We liked the sticky feeling and the sounds that accompanied us as we hopped our way around the farm. We hid from well meaning adults who tried in vain to reunite us with our rainboots. When the sun came back out, we were fascinated by deep cracks that had formed on the hard surface and imagined ourselves on another planet. I didn’t know why it made my mom cry, but I could tell there was a problem in our paradise.

Later I understood; how this hard shell on the surface of the earth ensured the runoff of the next downpour, setting up the cycle of flood and drought that our community knew so well. It was a time when rain in our county provoked as much grief as celebration; a thirst in the land that a history of bad farming practices guaranteed would never be quenched.

“Jake”, Amy would say, with a soft patience carefully cultivated over years of friendship, “you’ll realize soon enough that everything you ever needed was right here all along”.

She started telling me this in high school, while I was boldly sharing plans for my great escape from Peosta, a town whose proud claim that it was in the ‘middle of everywhere’ left me unconvinced. I postured with the bravado of a card player who’d been dealt a bad hand and was still going all in. Amy could see right through me. We walked home together then, sometimes holding hands if the feelings were flowing both ways, but never more than that. She had a good nature and good sense. I’ve never seen anyone prettier; not then or since. She had everything that was going to get in the way of where I wanted to go. One day I slipped through those deep cracks in the ground and rode a river of topsoil out of there, fast.

The road out of town had been made easy for me. Exploiting my natural athletic talents was simpler than the alternative; a punishing drama of pretending to make a living amidst the carefully arranged hardships of annual agriculture. It had become a way of life that produced a clear return for agrochemical companies in exchange for a lifetime of servitude from farmers who honoured their exponentially accumulating debts.

At college it was further simplified: physical risk yields instant rewards. Bowls of opioids, like my great-aunt’s candy dish, made readily accessible on the desk of my equally accommodating football coach. His comforting assurances justified a regular habit of filling my pockets with a Quarterback’s little helper, no up-front payment required. There was more relief in those pills than the best protection a 300-pound offensive lineman could offer. I was there after all to contribute, to compete, to help my team. The less I was on the field the less productive I could be. If we didn’t win, it hung on my shoulders alone, a heavy burden to carry. I also had the lion’s share of glory channeled my way when we prevailed. My teammates wordlessly accumulated their own lifetime of injuries, as I executed the game plan.

That blissful fog: nothing had compared to it before or since, quickly taking all my pain away on a cloud that never let me touch the ground. On game day when I had to be clean, the cheering crowd carried me through. And those girls; the jam on my sandwich that I greedily devoured. I used them up too, pretending I was their ticket out of nowhere. I suppose I was too high then to remember or to care.

Amy was accepted on academic scholarship to the University of Iowa the same year I was recruited to join their football program. We hadn’t spoken about it, but we didn’t need to; news travelled fast in Peosta. I heard that she was living at home to help with the farm while I decided to move to student housing in Cedar Rapids. Every now and then over the next few years I saw her on campus as she headed into the Developmental Psychology lab close to our practice facility at the athletic centre. I managed to avoid eye contact. The day I bumped into her, knocking her books from her arms when I turned, laughing, from a crowd of friends scheming to skip class, startled me. It shattered the independent picture of myself I was creating, reflected on my junior year football card; the one where I appeared to be ascending into the clouds with light streaming behind me, some sort of football Jesus, my polished helmet gleaming in the sun.

“Jake”, she said, with surprise and a kind smile. Just my name, no other comments, no ‘how are you doing?’, no updates from home. I wasn’t sure how to respond. On the surface it was nothing, but in the absence of small talk it felt profound, like she was calling me out, calling me home. I had an anxious moment of self-conscious awareness. Amy looked at me and I felt revealed, seen, right through to my inner core that the armour of my football gear had closely hidden.

I helped her to pick up her things, muttering a quick apology as I jogged to catch up with my crew. I remember the look on her face. Not judging, but hurt, or, maybe disappointed, by how bluntly I moved on, barely acknowledging her presence. I shook off the feeling later with my friends at the bar. A few beers, some oxycodone, a couple of percocets. I was riding high above the ground again and thoughts of Amy retreated to some distant corner of my mind.

After that encounter I completely silenced the last bit of her echoing voice that had followed me on the 151-S from Peosta to Cedar Rapids. I blunted it with painkillers and replaced it with adrenaline generated by a deep animosity directed at my enemies on the field, kids from other colleges who were obstacles in the path of where I was headed. No one was going to send me back to that place where I was treated like dirt, a local hick who didn’t know shit, someone stupid enough to suffer at the hands of agriculture and never earn a living.

Football gave me a sense of pride, although I can’t recall it now. In my senior year I earned the starter spot and played with a furious intensity to ensure I kept it. My coach fed off my rage, converting it into raucous locker room celebrations where I was held up as an example of what any man should aspire to become: focused, heartless, vicious. “Tear his head off and throw it back in his face” was our pre-game chant, breaking out of the huddle to act out our ‘eye-for-an-eye’ brutality as results piled up in the win column. I took no sacks until the last game that season, my uniform was spotless. Dirt was the great equalizer of all relations and steering clear from it was my chosen path forward.

The day a defensive lineman broke through our formation and threw me to the ground, tearing the pelvic muscles from my hip bones, I knew it was over. I didn’t need to see the x-rays; I could feel that my body was broken for good. The last two operations in my freshman and sophomore years had created a weakness that the surgeon had warned me would never fully heal. He said the best he could do now was to patch me up. He told me to forget about my bowl game dreams and pray that the stitching would heal well enough for me to go early in the draft, but I’d given up on church years earlier and the scouts sniffed it out at the combine.

Undrafted. Cut loose. A washed-up star college QB, a has-been whose sorry bones refused to carry him to the professional ranks. It’s still painful to recall. The price I paid to end up damaged goods. The realization of what I’d done and where I’d been. A pariah with former teammates and old friends. Everyone steered clear of me, afraid of some voodoo that might infect them too. I was the unhappy ending no one wanted to believe was possible.

Cut off from my supply of adoration and medication, unable to go backward or forward, I had no Plan B, no energy to push against the current trajectory of my life for an uncertain future I wasn’t sure I wanted. It took an overdose on opioids laced with fentanyl and the thankful grace of a roommate who called 911 to begin my painful journey of self-discovery and agricultural repair.

Amy came to visit me in the hospital, but only once. I pretended to sleep while she cried beside me. I was too ashamed to look at her, for her to see me; to admit what I had become. She whispered one sentence in my ear before she left, pressing a small bag in my hand and squeezing it tight with her fingers wrapped warmly over mine.

“Jake Hutter, here’s the cure for your solastalgia”.

I could have grabbed her and kissed her right there. I could have pleaded for her to forgive what I was, how weak and stupid I had been. But I wasn’t strong enough then to own up to what I didn’t yet understand.

I’m ashamed now to admit that the tremor of excitement I felt at opening the pouch was not innocent. I was hoping in my delusion of withdrawal that she had, in a great act of compassion, given me some magical elixir, a tonic that that could erase all my pain in in one clear snort. When she was barely down the hallway, I opened my eyes and tore it open, sniffing hard, agitated, tasting the contents inside. I shook my head and my eyes teared up; the sensation was overpowering; smelling salts that woke me to the purpose of my life.

I stayed up all night, inhaling the aroma of the damp soil, running my fingers through it, placing it on my fingers, tongue, letting it roll to the back of my throat and dissolve in my cheek. This was pure stuff, wholesome, organic. There was no contamination from nearby industry, no taste of fertilizer, pesticides, or insecticides to be found. Dark and sumptuous, the smell slightly sweet with the aroma of geosmin, I instantly recognized this native prairie soil. It was taken from the small, undisturbed lot preserved by my great grandad and generations since, unaffected by and unconnected to our modern operations. It had been covered by perennials for thousands of years, before he had arrived with his wagon and family in tow, setting up homestead in Peosta; it was a font of ecological knowledge, an open classroom offering enlightenment for any farmer who cared to pay attention.

I stirred restlessly for the next 24 hours in a fever of torment and wicked dreams. When I awoke, I felt for the first time in years, a flicker of possibility that came from my heart. I wanted to fan it into a fire before I stood up to argue for my future. I didn’t say anything to anyone about it. I suppose I didn’t know what could be said. Everything that had been done couldn’t be undone. I had no real reason for hope, but reason wasn’t my purpose, reason didn’t drive me to change my life. It was that word, that one mysterious word that Amy had whispered to me before she left. Solastalgia. It was her promise that the soil could cure what ailed me. It was her ability to see my best self, beyond the broken person who I’d become.

I would have laughed myself out of the room with those sentimental thoughts when I left for Cedar Rapids after high school, but I didn’t judge things so harshly anymore. Experience had taught me that I needed the mercy of idealism more than a shield of cynicism. Amy planted a seed of possibility in a deeper place than I could reach. I let it grow its way toward me. I watered it with an aquifer of my own unshed tears until I felt like I had something inside of me again; something to give.

I don’t know exactly why I decided to return to the farm when I was finally released from the hospital. It would have been easier to move somewhere entirely new, to make a fresh start. Was it a sense of unfinished business? A retreat to lick my wounds? The hope that some scrap of a world I once believed in might still remain? The sound of solastalgia stirred in my brain, the diagnosis Amy had whispered that night; a kiss on her lips that was waiting to be collected somewhere else.

My dad didn’t know much about regenerative systems or permaculture practices and never taught me any of those ways. He’d never cared too much for the plow himself, but it wasn’t from a commitment to no-till. When I crawled away from the wreckage of my college dreams, there was an apathy that settled in between us, replacing the eager conversations of my youth; old ambitions sparked by Friday night high school football games that had fueled our hope of a different future.

“Jake”, he would say to me with his shoulders hanging down, burdened by his role as a harbinger of doom. “It’s a useless struggle, I tell you. All a farmers’ life and money…devoured, gone, eaten up fighting against drought, pestilence, and disease. It’s more of a punishment than a way of living.”

He didn’t speak to me about my plans anymore and in return I didn’t pretend to have any. I sat in the dark for the first few months, brooding on what I’d lost, trying to understand why I was there and what to do next. In hindsight I suppose it was my first attempt to listen to the needs of our landscape and to allow our farm to adapt to my new choice of practices.

I wasn’t like my father, running from the past. I had believed that there was good in my grandad’s operations, but he had no vision of how to bring the best of those old days forward to change the future.

When my grandad died in my first year of high school, my dad’s own best intentions got in between me and my healthy soil relations. Everything my grandad had taught me in those early days on the farm was quickly replaced with my dad’s own ideas: a college degree in agribusiness, a football scholarship to pay for it and large-scale production opportunities that would follow. It was as if my grandad’s passing had released the pressure built up in our enterprise, the gradual decline in profit and yield over a lifetime of work. In the absence of any viable alternatives, my dad was completely signed up for the modern program: GMOs, nitrogen-based fertilizers, pesticides, fungicides, and herbicides. US farm policy was an invisible hand that firmly shaped my life, more than nature or nurture.

After weeks of debating my next step, I picked up the phone and called Amy. My fingers dialed her number without thinking; it hadn’t changed. I was relieved to hear her answer and eagerly demanded more information.

“Solastalgia, Amy, what did you mean? Why did you say that dirt was the cure?”

She was angry.

“Is that what you think I gave you? Dirt? Dirt is soil without life Jake. I didn’t give you no bag of dirt.”

Her hard reply caught me by surprise.

“And how dare you call me up and ask me the answer for anything? What about, “how have you been”? What about “I’m sorry for being such an asshole to you and everyone else I’ve been treating like nothing more than dirt since I left for school.”

I sat in silence, realizing that she was right. I was so urgently in need of something to preserve myself. I hadn’t taken a second to think of anyone else for a very long time.

“I’m sorry Amy, it’s just that…”

She interrupted my feeble apology with a swift rebuke.

“All our lives you’ve come to me for inspiration whenever you need a quick fix; like I’m some font of knowledge or comfort. Then you hide from me when you’re hell bent on doing whatever stupid thing you’ve decided to want next”.

Her words stung but I didn’t interrupt. I was hearing something that I had never heard before, that I was finally ready to hear.

“I’m not some ideal you have of mother nature, a breast you can burrow in to make everything wholesome and good again. And I’m not a loving mirror reflecting your true self back to you, so stop running away from me whenever you see something in yourself that you don’t like”.

“Amy, I’m really sorry”.

“Jake, forget sorry. This is much bigger than any apology. You’ve got to turn your eyes out from your own damn self and see everything that you have around you. I’m a human being with real feelings. We were friends. Call me when you figure that out.”

Her voice cracked and I was left alone with a dial tone. I listened to that high pitched sound for over an hour to avoid the pain of silence that I knew would shake my body when I put the receiver back in the base.

I started my new journey that afternoon with some simple research on the computer before I immersed myself in the ecosystem of our farm that would become my best teacher. Solastalgia, it turned out, wasn’t so cryptic after all. I only had to look.

A philosopher had come up with the word to describe a special kind of ecological grief, feelings of nostalgia, desolation, and yearning for solace. It was the constant homesickness that I felt even when I was at home, an anxiety that was provoked…. because my home environment had been changed or even destroyed.

It had been naïve, or perhaps more truthfully, ignorant, to think that Amy would take each step with me, that I could use her to do the inner work that needed to be done, all the stuff I didn’t want to face up to. She was right to hang up on me, to cut me off from a line to more excuses and delays. I realized that soon after and was grateful for the gift she had given me, a caring nudge in the right direction.

Looking back on it from a clearer vantage point today, I suppose my saving grace was my senses. I liked the smell of dirt and sweat, the communion of working with others who were close to the soil. Even playing football, when the exaltation of a good performance made me feel that I couldn’t get further from where I’d come, I knew that I couldn’t throw a pass unless my feet were planted firmly on the ground. It seemed to be some intuition of my future survival.

Over the days and years that followed, I grew to realize something Amy already knew when we were back in high school. Football wasn’t my dream. It was a compromise, brokered by my father, as a way out of our old life, a vehicle through a dying landscape that was going to hog shit around us all. My dad wanted me to use my physical talents to make my way toward a new future, one where I could run the machinery, but he hadn’t counted on me getting caught up in the gears. It helped when I figured that out, to know that I hadn’t lost the core of what he and I were both after, only the map of how to get there.

I didn’t call on Amy again until I had something to show her, something that would prove I’d really listened. The word she had whispered haunted me for years, it was a companion to my reparations to the soil, my first act of care. It was more than a strong breeze blowing through the farm that carried me back days after that phone call to the place where my granddad’s plow once stood. It was…I’m still not sure entirely what it was. But I know that I heard voices, as if there was a crowd in the stadium again, anticipating a Hail Mary pass in the fourth quarter. I knew what I needed to do, the conviction of my own prime directive to care for the land, for people, for justice. There was no work around, no quick fix. There was no easy dodge to forget the misery I’d felt and that I’d caused. I had to go straight through. I needed to rebuild my soil relations from the ground up.

The problem of the plow was that it was the start of all this trouble. It went well back to some early advice from old books and outdated ideas of how to meet nature head on and show it who was boss. To the violent energy that called men to tear up the structure of the soil, to do their own bidding, to ignore the wisdom of the earth, to challenge the intelligence of seeds that knew where to plant themselves, to wipe out perennials that grew naturally under tree crops whose yield was easy and full. An order to annually destroy all of creation in a misguided effort to endlessly increase yield.

This ‘agriculture of eradication’ that became the neighbourly approach, every living being annihilated until an eerie stillness set across fields that no longer buzzed with pollinators or pests. The deafening silence of a death zone my dad had affectionately referred to as ‘the farm’. I threw it out, all of it, that day I hung up the phone with Amy. No till, no chemicals, no assault on ecological rules. It was the purest feeling of longing that filled my heart, desire without any shame. I felt patient and unstoppable. I burned for the land with an unrelenting need, to be close to the earth was my only preoccupation. These amends I made were preparations of a sort, opening myself to receive her love.

This was the reconciliation that took place before the restoration of a devastated landscape. I could sense I was coming through to the straightaway from a long corner I’d been turning for years. The lure of old habits was manageable now, firmly entangled in these carefully established roots. And now this scene I surveyed today, a diversity of perennials: fruit and nut trees, vines, berries, and fungi. A cropping system that was both wild pollinator habitat and conservation practice; the lushness and abundance was staggering. I was no longer trying to outproduce my ecology.

May Basket Day. It was a day filled with simple pleasures and manageable adversities. I put together the traditional Iowan offering of flowers that were meant to be delivered to a neighbour in a carefully arranged hamper. As kids we had served as willing couriers, dropping our gifts to each other, and then running away before the messenger could be seen. I placed the basket on the step and rang Amy’s doorbell, retreating around the corner. When she came out for the delivery, I re-appeared before her, standing my ground, hat in hand, asking her to hear me out.

“I’ve prepared the soil. I’ve gone as far as I can on my own Amy. I’m asking you now because I still don’t have the cure. Can you help me?”.

Amy took my hand and led me behind her house, across the shortcut to our farm, to where she had seen me work from season to season, patiently waiting for what she believed in, for what she knew would emerge with time. She stopped in the middle of the landscape that I had carefully rebuilt with the guidance of ecological wisdom and turned toward me.

“The cure is simple Jake. I can’t help you alone, but I can help us. The cure…it’s not in me, Jake. It’s not in you either. It’s between us, between all of us; it’s in our relations”, she smiled, planting herself gently into the damp ground, soil so rich with dark organics it appeared a purplish black.

Her body was a revelation, reclining on the bed that nature had made, the work done by a billion microbes, plants, an ecology that was pulling together effortlessly in the direction we needed to go.

I don’t know why I ever fought so hard before against such generous help. I just couldn’t see it, I suppose. My spirit had been drained by a world that believed in linear pathways, but it was revitalized that night in the cycles of the soil; nature repaired herself and Amy and I followed.

Rain fell, slowly on us at first, then much harder. It absorbed easily into the porous soil that could finally receive its relief. We were heady with delirious anticipation, building from the ground up. The fertility of the earth had returned, and we were in it.

Read Less

Land: Mangrove Maj by Martin Hastie

Water is a global issue. But there’s loads of salt water… Can salt water be used to grow crops in some circumstances?

Read More

These things creep up on you without you noticing. One minute, there you are minding your own oil-trading business, racking up the millions (and the rest!) in your numbered bank accounts, feted by fawning industry admirers and sycophantic media hangers-on. Then, before you know it, all of a sudden you are Mr Unpopular, a leper bell around your neck, featuring at number seven in The Guardian’s much-trumpeted list of the Top Ten Existential Threats to the Global Environment.

It would be fanciful to suggest that my origins were humble – a first-rate if rather troubled education at Lancing College, a knight-of-the-realm father rubbing shoulders with ministers and minor royals. (Papa was, rather unfortunately, disgraced in later life, but the point still stands.) When you exist only in these rarefied environs, the advantages that you have over others are neither apparent nor of any particular concern. Indeed, the first time I read an opinion piece accusing me of being posh and overprivileged, I almost spat out my 1969 Louis Roeder Cristal Millesime Brut. Later in life, though, even I had to appreciate that such a charge is difficult to counter when you happen to be in possession of your very own island.

As islands go, it was never much to write home about. Small, scrubby, over-grazed with stringy goats. It was really neither use nor ornament. The island’s one redeeming feature was the not-quite-golden beach on its south-facing shoreline, and in those early days, my darling wife, Jeane, and I spent many a sun-kissed afternoon seduced by the lapping waves, surrounded almost entirely by unspoilt nature, feeling as though the world was ours alone. Jeane could happily idle away countless hours watching tiny sand crabs scuttling from hole to hole like batters sprinting between bases, while I liked to cheer on the mudskippers as they used their minuscule but powerful forelimbs to hoist themselves through the thick gluey sludge beneath the jetty. If often gave me cause to ponder whether these extraordinary creatures were observing me just as I them, peering up through inquisitive eyes and wondering what on earth is this peculiar man staring at?

My fortune, as I mentioned, came from oil, amassed via a combination of good luck and fortuitous timing, a smattering of expertise and a dedication to the job that very nearly killed me. Aged just forty-four, my heart decided it had had more than enough of my work-work-work lifestyle and tried its best to condemn me to an early grave. Somehow, to even my doctors’ amazement, I pulled through. Jeane’s immense relief was tempered by the fact that my first act upon opening my eyes in the Intensive Care Unit was to ask if I’d missed any important messages from the office. She was also a little nonplussed by my referring, tongue-in-cheek, to my revival as ‘the Resurrection’. But I think, all in all, she was glad to have me back.

I am not a man of any great religious conviction. Agnosticism runs through my family like male pattern baldness. In his early seventies, my father collapsed and died on the pavement outside the village Post Office. Thereafter, my equally nonreligious mother, who had stood by Papa after both his financial and infidelity scandals, said a quiet little prayer every time she passed that gleaming red postbox. It struck me as unlikely that my father’s spirit should choose to haunt the very place where his life was cut short. Having said that, given his disdain for the shoddy customer service he always complained of receiving there and his willingness to hold a grudge, I wouldn’t put it past the old devil to be hanging around and putting the willies up the counter staff. In any case, it brought my mother some much-needed solace throughout her final years, and that was all that really mattered.

Love is an incredible thing. When Jeane started giving her speeches, the situation caused much consternation among my peers. ‘She must be such an embarrassment to you.’ ‘She’s going to give you another heart-attack at this rate.’ And it was true – at first it did cause a tremendous degree of difficulty. The environmental concerns she was espousing were entirely at odds with the practices necessary for my businesses to function. It would be untrue to say that I felt no guilt about the damage my companies were causing around the world, but I found myself able to blank it all out, to pretend it wasn’t happening. In those days, I wouldn’t have known a mangrove terrace from a palm oil plantation. It makes you wonder why she married me – it was certainly never about the money. I suppose it must have been love.

From the beginning, I admired Jeane’s freedom of spirit. On our very first date, I can vividly remember her outlining her ambitions to help save the northern white rhinoceros from extinction, speaking with rare passion, beguiling me with that delightful, soft Scottish accent that brought the blood to my cheeks and weakened my knees. It was clear from the first time she stood at a podium that she was a born orator. Watching her address the delegates at COP 20 in Lima, I could see that she held her audience rapt throughout. They were spellbound by her performance, dazzled by her words. Our daughter, Sarah Jane, was beyond proud. Alistair, a bit younger and still in those awkward teenage years, was horrified. Me? Well, I suppose it should have irked me that she was, essentially, trying to bring down my industry. But she wasn’t really, of course – her speeches simply stressed the need to adapt to a changing world. Either way, I couldn’t take my eyes off her in that long baggy grey dress and those heavy black Dr. Martens.

At first, as is the way of these things, Jeane received far worse press than I did. She was categorised as a tree-hugging do-gooder (as if these are bad things). But then came the Guardian article naming me Public Enemy Number 7, which was a watershed moment and no mistake. Naturally, the write-up mentioned Jeane – in fact, it was quite clear that her activism was the only reason I was featured at all. It gave the picture editor an opportunity to insert a photograph of her beautiful face into the newspaper – much better for business than my ugly mug. After that, the tabloids latched onto us. Overnight I went from being the distinguished oil magnate Oliver Frankland to Oily Olly, while she, of course, was dubbed Green Jeane. It caused some friction, I won’t lie, but not as much as you might think. Perhaps it was my near-death experience, or maybe it was Jeane’s remarkable powers of persuasion, but something had changed and I was starting, slowly but surely, to edge towards her way of thinking.

At the COP 20 meeting, Jeane had grown friendly with Majid, a curious man of astonishing intellect from Abu Dhabi who was better known, it transpired, as Mangrove Maj. He’s large and barrel-chested, intense but exuberant, and his entire bulky frame shakes whenever he laughs, which is often. Jeane was bowled over by his enthusiasm and knowledge and was keen for me to meet him. It soon became apparent why.

‘He’s looking for someone who owns an island. I mean, that’s ridiculous, isn’t it? That’s us!’

Some strange providence must have brought us all together, that’s all I could think. A man on the lookout for somebody who owns an island happens to find themselves chatting to just such a person. I can’t imagine that sort of thing happens every day.

‘It’s not like we even do anything with the island anymore.’

She was right, of course. There had been a time when we had entertained the great and the good (and the utterly appalling), but age and misanthropy had caught up with me and I no longer had much desire to play mine host. Coastal erosion had set in anyway – a result of increasing storms, and I’d accepted it might one day be lost to sea rise.

‘Just say you’ll speak to him,’ she badgered me, over and over, until I eventually made room in my busy schedule for a call. And thank God I did. Speaking to Mangrove Maj changed my life. I can only hope it’s going to eventually change millions of other lives, too.

‘Have you ever heard of mangrove terraces?’ he asked me after a few strained pleasantries.

‘Yes, I think so – it’s a golf resort in Barbados,’ I replied, half-joking. Of course I hadn’t heard of mangrove terraces.

‘Well, strap yourself in,’ he said. I could sense the smile in his voice. ‘You’re about to hear absolutely everything about them.’

I don’t think he stopped talking again for around forty-five minutes. Their carbon-capturing potential, how they can protect against storm surges, increasing resilience of coastal areas to climate change.

We started work almost immediately. In the beginning, securing funding proved difficult. I pumped a million dollars in to start things off, as no one else would touch this outlandish idea, this absurd novelty. The tiny start-up team delivered, three months late, a large submersible pump, 500kW of solar panels, two kilometres of plastic pipe, the connectors, a supervisor (appointed directly by Mangrove Maj), fifty litres of sun cream, thirty sun hats and ten Indonesian labourers. Oh, and twenty thousand mangrove seedlings. They spent three months laying pipe, building berms, pumping water and, eventually, planting mangroves. The mangroves were laid out not in coastal waters, as is almost always the case, but in terraces, like rice.

Environmentally, intentionally salting dry land was a little dubious, but it was a private island so that was much less of a problem. An unforgiving tropical storm led to flash floods that washed away some of the mangroves, but they flowed down the gullies and were collected in the grid at the bottom. Large seedlings were replanted the following day, and, luckily, mangroves grow rather quickly. After a year, most were doing well, and the ‘salty forest’ was coming along nicely. The terraces were watered with sea water, which was pumped up from the beach using solar power and distributed through small trenches designed by an old rice farmer in Bali with whom Mangrove Maj had become acquainted while he was over there for COP 13. The old man’s trenches worked beautifully.

There had been concerns about the goats, but it seemed that they weren’t partial to ready salted leaves and they mostly left the seedlings alone. After the third year, a trial batch of prawns was added to some of the terrace pools near the sea. This was particularly good news for me – Jeane and I ate prawns on our first date and they subsequently became ‘our thing’, so I was devastated to learn that they were an environmental disaster area. Mangrove Maj explained to me that it’s the trawling that causes the damage, comparing it to picking strawberries with a bulldozer. But these prawns fared really rather well and were harvested by opening the sluice gate, flushing the pond with sea water and catching them in a simple net in the gully. Gravity did most of the work. Sold at the local fish market, the prawns were snapped up in ten minutes flat like hot tickets to the Philharmonic. All of the ponds now have prawns and/or fish, and the unbothered aquaponics system reduces the feed that they require. It seems to help the trees, as well. Seafood has been a major part of the revenue for the project, particularly in the early stages.

After the fourth year, a small crop of wood was taken from the largest trees. This wood was made into biochar using a homemade kiln on the beach. Not so efficient, but easy to use. The biochar was soaked in chicken manure, left to dry in the sun and then added to the fallow ponds and the new seedling areas. It works a treat, though the chicken manure job was not the most popular. It’s rather more popular now, though, as it pays double. After six years, and five rounds of expansion, the first serious coppicing was done by a local team hired from a nearby island. They cut strips through the forest, only harvesting a third of the trees, and hauled the wood down to the beach with a jury-rigged zip wire and a winch – a system that has grown ever more streamlined with each repetition. The brash was turned into biochar on the island as before, and the three hundred tonnes of logs were taken to a gathering yard in the nearest major port. To transport these small shipments, fabulous little wooden coasters called pinisis, halfway between a dhow and a pirate ship and a real blast from the past, were deployed.

The three hundred tonnes of logs joined a pile of twenty-five thousand tonnes from other projects and sources and was shipped to a site in Abu Dhabi operated by Mangrove Maj and his business partners. This trial transferred the logs inland to a barren, salty area where a massive pit had been dug. The wood was laid in the pit, which was then filled with strong brine from the nearby Reverse Osmosis plant. This super-strong brine gradually evaporates and pickles the wood, preserving it for thousands of years, and is a neat shortcut that enables the maximum amount of carbon to be stored with the minimum amount of combustion. Biochar is great, and is widely used throughout this and other processes, but it does still release some CO2 while making black, non-rotting carbon for soil improvement and sequestration. There is an ongoing debate about whether the wood pickling or the biochar is most efficient, and there are arguments for both sides. No doubt there will be for many years to come. Both systems are making a positive contribution in slightly different ways.

Now, after seven years, the island is 50% salty forest and 50% what it was before. The ready salted goats were sold a couple of years ago. The whole island has bounced back, with a surprising variety of plants, animals and birds. Islands are always a bit narrow in terms of the wildlife they can host, but in this case, it has been made up for by a bold abundance. There is a surfeit of fascinating little birds and a cracking selection of insects.

We worked hard, carefully choosing watersheds and checking aquifers, to ensure that the seawater does not damage anything that would be better left undisturbed. Most of the mangrove wood is made into biochar for both local use and export. We have, I think, thought of everything.

And yet, I can sense you thinking, there appears to have been a media blackout about all of this. Where is the Guardian article slapping you on the back for this monumental achievement and celebrating your Damascene transformation from ecological pantomime villain to spearhead of the upcoming mangrove terrace revolution?

Well the project is still, as we speak, top secret.

In fact, beyond knowing that I had agreed to talk to Mangrove Maj, even Jeane knew nothing about any of this. A brain tumour – swift, merciless, devastating – stole her away from me three days before that initial conversation. It is, perhaps, poetic that my greatest triumph is also my greatest tragedy. You will have read the various obituaries at the time, of course. Universally glowing, as befits. Even those rags that had vilified her in life deified her in death. ‘’Green Jeane’ didn’t quite live long enough to change the world,’ read the tribute in The Telegraph, ‘but she laid a path so that others might.’ Sarah Jane has, of course, followed in her mother’s footsteps. Our hugely talented daughter’s debut book takes pride of place on my bookcase and is always prominently displayed in the background whenever I have a Zoom meeting. Alistair runs half-marathons to raise money for environmental causes in his mother’s name.

The truth is, I can take no credit for any of this. She changed everything. Well, she and Mangrove Maj, of course. He told me that he intentionally sought Jeane out at COP 20 because he’d read that we owned an island. He also told me that it was the best thing he ever did.

Although I can no longer quite face eating them, Jeane has opened up a world where people can munch prawns, guilt-free, to their heart’s content. (Unless they’re vegans, of course.)

I still see her radiant smile in the faces of the grandchildren she never knew. And that’s what matters, isn’t it? Yes, I’ll always wish I’d acted sooner. And yes, I’ll never quite shake the feeling that I took her for granted. But we’ll all be gone one day. What we’re working for, what we’re fighting for, isn’t for us. It’s for those future generations yet to be born. That’s why we’re sequestering carbon, installing seawalls, helping wildlife to prosper. That’s what it’s all about.

Next week, we’re going public. It’s finally time. We wanted to prove beyond any doubt that this could really work over a sustained period. For the rest of the coastal mangrove terrace industry, our worked example will help to secure funding for other sites around the world. The potential is unimaginable.

Meanwhile, Mangrove Maj has made it clear that he wants no publicity. When the media circus hits town, he’ll be lying low, working on yet more pioneering ideas of how we can make the mangrove terraces even more effective. And me? I’ll be where I usually am these days: on the south-facing shoreline, watching those incredible nippy sand crabs as they race back-and-forth across the not-quite-golden sand, saying a quiet little prayer.

Read Less

Thanks for reading today’s stories. We will be back tomorrow with more.